By Marisa Michael, MSc, RDN, CSSD

If you spend any time within the climbing community, you’ll start to hear people tell you to lose weight to climb better. Although this message is usually not helpful or accurate, it’s pervasive. You’ll also hear stories of eating disorders, and how people trying to lose weight ended up with disordered eating patterns.

It’s not hard to do a Google search and find climbers from recreational to elite sharing their disordered eating stories. While raising awareness is important, we also need solutions.

Here are four ideas you can try to become a part of the solution.

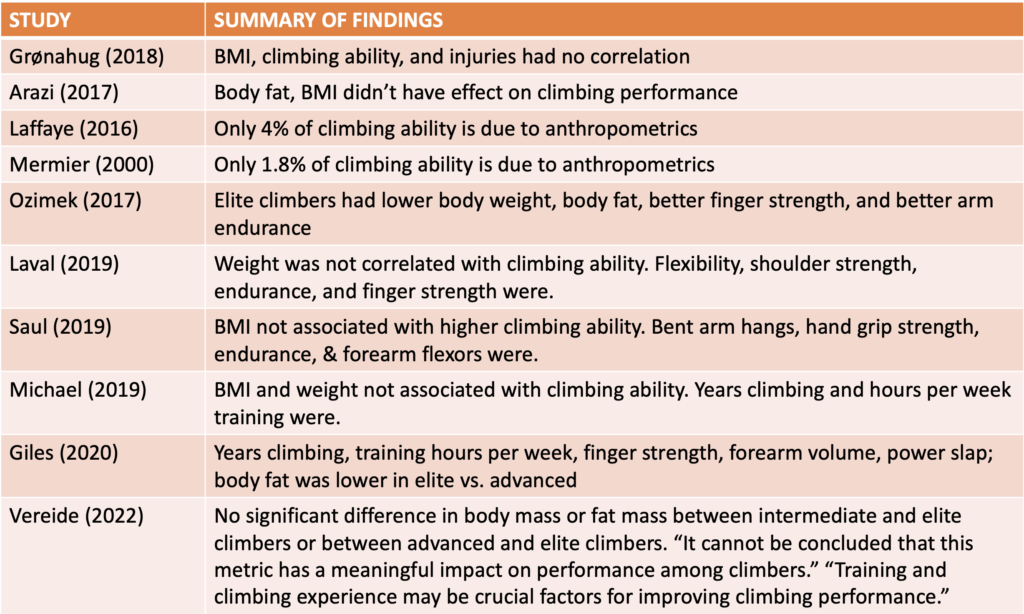

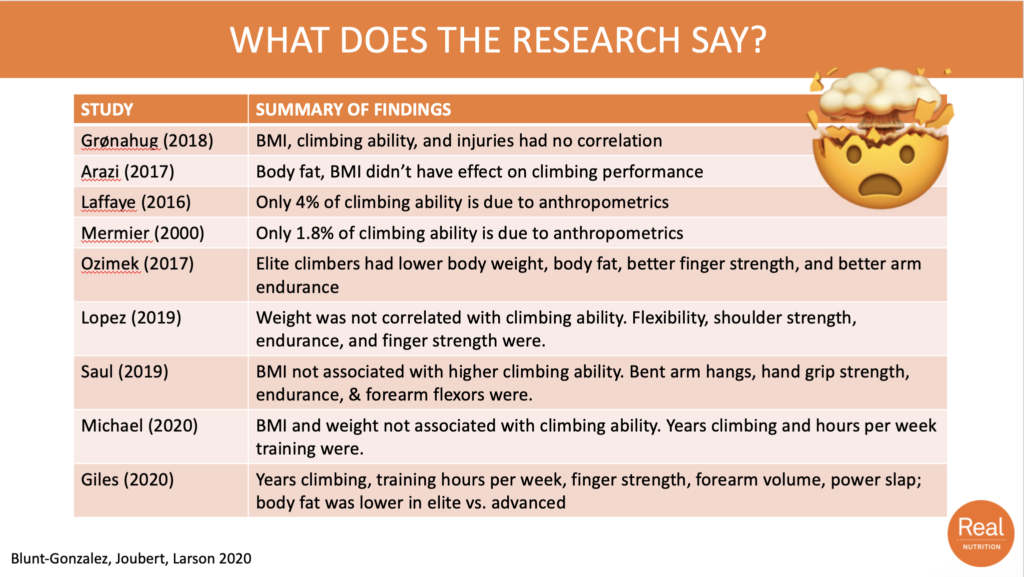

Solution 1: Understand the research behind weight and climbing performance.

There is not research to support losing weight in order to enhance climbing performance. There is research that suggests weight is not a key performance indicator.

While a climber may benefit from losing fat mass (if they have excess fat mass to lose), this isn’t the first approach many would want to take. This is because weight loss is not a neutral thing. It can lead to negative health outcomes, including Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs).

So yes, weight loss is a strategy, but it isn’t one to be applied without careful consideration. The good news is, research suggests that you can do a lot of other things to enhance climbing performance! And these carry less risk.

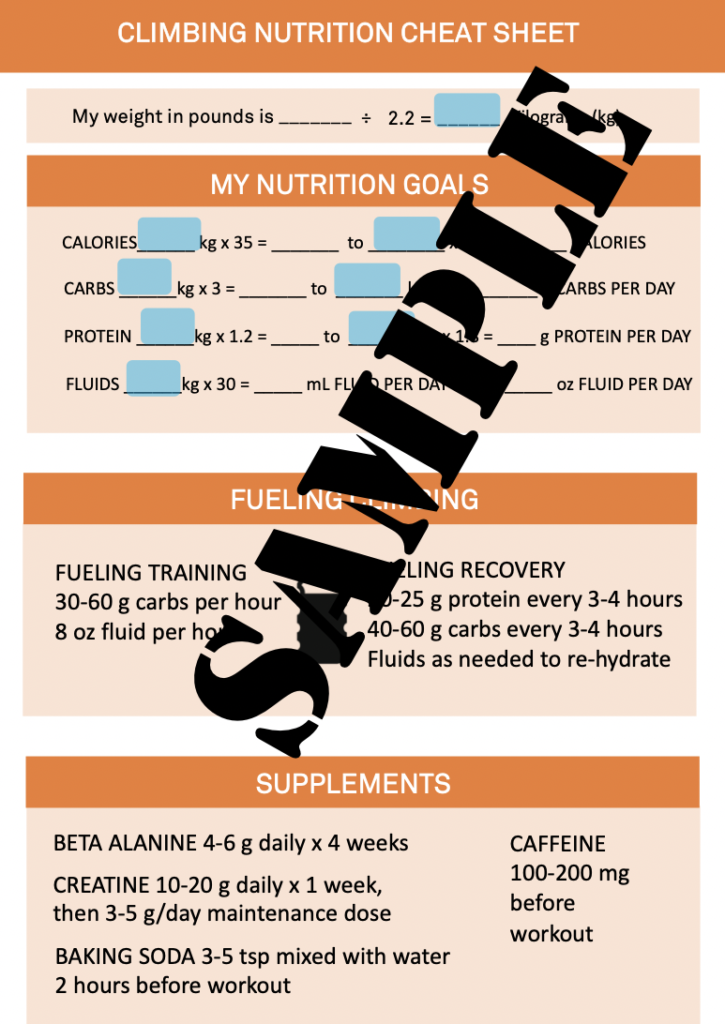

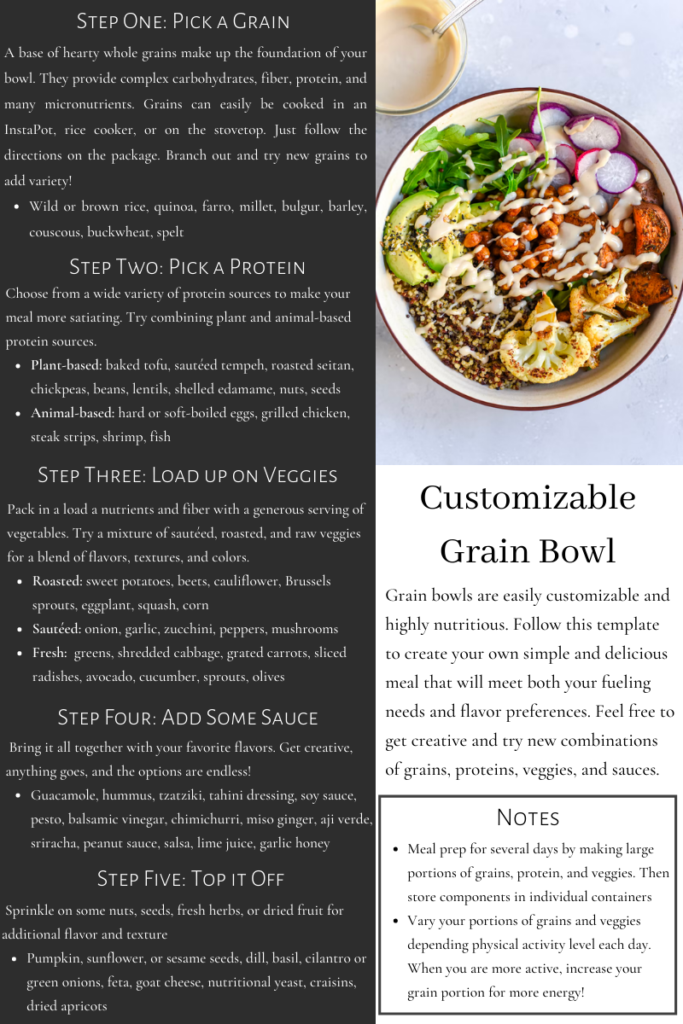

- Dial in on fueling & hydration

- Gain strength

- Improve flexibility

- Improve endurance

- Grow skills and technique

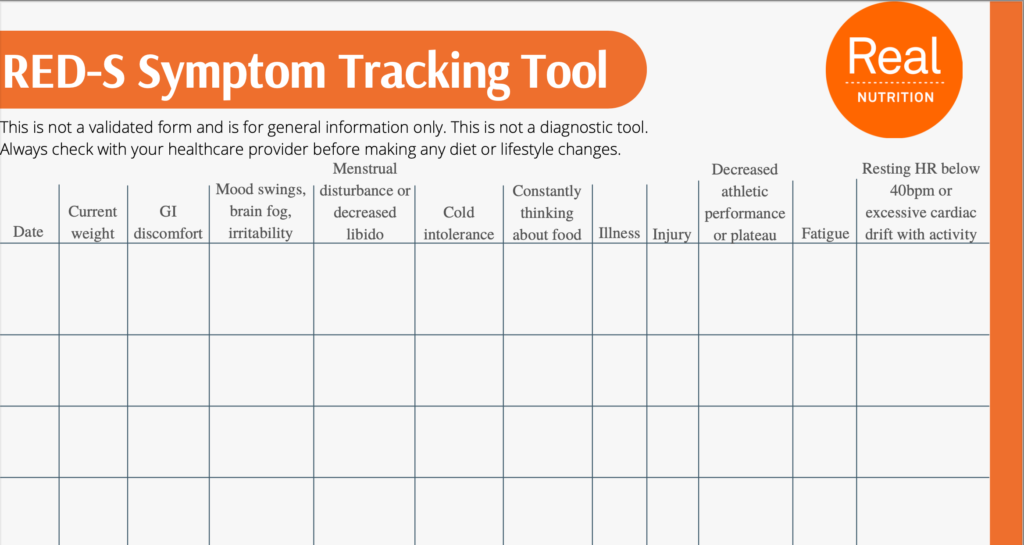

Solution 2: Know the signs and symptoms of disordered eating

Being a part of the solution means understanding what signs and symptoms to look for in a person who might be struggling.

Eating disorders don’t have a specific look. They are complex and each person experiences it differently. However, here are some common signs and symptoms:

- Weight changes (loss or gain)

- Changes in eating patterns (eliminating foods or food groups, skipping meals, eating in secret)

- Going to the bathroom after meals

- Having a lot of food rules (only organic, don’t eat past 6 pm, etc.)

- Difficulty regulating body temperature, blood sugar, or blood pressure

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

- Changes in bowel patterns (diarrhea, constipation, bloating, nausea)

- Inflexibility in food choices, especially at social events, traveling, or restaurants

- Thinking about food all the time

- Exercising to “earn” or “burn” calories

- Exercising beyond what a coach prescribes

- Plateaued or decreased training capacity, even when training consistently

- Frequent illness or injury

- Low energy, fatigue, difficulty concentrating

- Lack of motivation or “try hard”

Solution 3: Stay within your scope of practice

What does this look like?

For a climbing coach, this would mean simply to coach! Be a great coach, design training plans and schedules, coach on technique, flexibility, skill, endurance, etc. Stay within your scope and don’t instruct your climber on nutrition, hydration, medical needs, etc. Don’t tell a climber to lose weight or take supplements. Refer to a medical professional in your area when the climber’s needs fall outside of your scope. Have. a list of doctors, physical therapists, dietitians, etc. who can help the climber when they have a need beyond coaching.

For medical providers, stay within your own scope of practice. A doctor shouldn’t be giving in-depth nutrition advice. Save that for the sports dietitian. A dietitian shouldn’t be doing counseling–save that for the therapist. Staying within our scopes of practice keeps the climber safe and ensures they get correct information.

For climbers, this means to be a climber! You’re not a coach, dietitian or anything else. Staying within your scope could look like participating in comps and training with other climbers, encouraging fellow teammates, taking turns belaying, etc. This doesn’t mean giving diet or training advice.

For parents, it can be a huge challenge to stay “just” a parent. It’s tempting to do all the Google searches and podcast dives to find training and nutrition advice. However, most of it is wrong, and even if it’s correct, it takes skill and clinical judgment to be able to apply it appropriately. Stay within your parenting role by taking your climber to practices and comps, signing them up for whatever they need, purchasing their climbing gear, and being their cheerleader. You can be a valuable resource to help them find the right doctor, coach, therapist, or dietitian.

Solution 4: Say something if you suspect something

Although it can be awkward, if you truly suspect another person has disordered eating patterns, it’s prudent to say something. If it is a youth climber, adults have a special responsibility to keep them safe (medically and mentally).

Here is an example of what you could say in a fake scenario.

A youth climber skips snacks at the designated snack time during practice. She refused to eat at the restaurant with the team after an out-of-town comp. What should you do?

Answer: Approach the climber with compassion and facts. “I noticed you skip snacks and the restaurant meal. What’s going on?”

She may reveal that she can’t afford the snacks or meals. Or she may say that she is trying to skip meals to lose weight or “be healthy.” Or she may not even recognize something is wrong if she truly is struggling with disordered eating. If you suspect disordered eating, you can give her the name of a doctor and dietitian in the area. “Please see these providers. We want you to get a checkup to make sure you’re good to climb.”

Tips:

Use fact “I noticed that you ____”

Approach with compassion and care.

Have a plan ready with next steps.

Contact the National Eating Disorders Association for more help and tips.

For more resources, check out our Disordered Eating Resources tab on our website.

And if you’d like to work one-on-one with the dietitian, contact her at dietitian@realnutritionrdn.com or book an appointment online.

~This is general information only and not nutrition advice. Always talk with your healthcare provider before undergoing any diet or lifestyle change.